There was once on a time a King who had a daughter, and he caused a glass mountain to be made, and said that whosoever could cross to the other side of it without falling should have his daughter to wife.

Then there was one who loved the King’s daughter, and he asked the King if he might have her.

“Yes,” said the King; “if you can cross the mountain without falling, you shall have her.”

And the princess said she would go over it with him, and would hold him if he were about to fall.

So they set out together to go over it, and when they were half way up the princess slipped and fell, and the glass-mountain opened and shut her up inside it, and her betrothed could not see where she had gone, for the mountain closed immediately.

Then he wept and lamented much, and the King was miserable too, and had the mountain broken open where she had been lost, and though the would be able to get her out again, but they could not find the place into which she had fallen.

Meanwhile the King’s daughter had fallen quite deep down into the earth into a great cave.

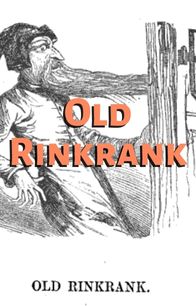

An old fellow with a very long gray beard came to meet her, and told her that if she would be his servant and do everything he bade her, she might live, if not he would kill her.

So she did all he bade her.

In the mornings he took his ladder out of his pocket, and set it up against the mountain and climbed to the top by its help, and then he drew up the ladder after him.

The princess had to cook his dinner, make his bed, and do all his work, and when he came home again he always brought with him a heap of gold and silver.

When she had lived with him for many years, and had grown quite old, he called her Mother Mansrot, and she had to call him Old Rinkrank.

Then once when he was out, and she had made his bed and washed his dishes, she shut the doors and windows all fast, and there was one little window through which the light shone in, and this she left open.

When Old Rinkrank came home, he knocked at his door, and cried, “Mother Mansrot, open the door for me.”

“No,” said she, “Old Rinkrank, I will not open the door for thee.”

Then he said,

“Here stand I, poor Rinkrank,

On my seventeen long shanks,

On my weary, worn-out foot,

Wash my dishes, Mother Mansrot.”

“I have washed thy dishes already,” said she. Then again he said,

“Here stand I, poor Rinkrank,

On my seventeen long shanks,

On my weary, worn-out foot,

Make me my bed, Mother Mansrot.”

“I have made thy bed already,” said she. Then again he said,

“Here stand I, poor Rinkrank,

On my seventeen long shanks,

On my weary, worn-out foot,

Open the door, Mother Mansrot.”

Then he ran all round his house, and saw that the little window was open, and thought, “I will look in and see what she can be about, and why she will not open the door for me.”

He tried to peep in, but could not get his head through because of his long beard.

So he first put his beard through the open window, but just as he had got it through, Mother Mansrot came by and pulled the window down with a cord which she had tied to it, and his beard was shut fast in it.

Then he began to cry most piteously, for it hurt him very much, and to entreat her to release him again.

But she said not until he gave her the ladder with which he ascended the mountain.

Then, whether he would or not, he had to tell her where the ladder was.

And she fastened a very long ribbon to the window, and then she set up the ladder, and ascended the mountain, and when she was at the top of it she opened the window.

She went to her father, and told him all that had happened to her.

The King rejoiced greatly, and her betrothed was still there, and they went and dug up the mountain, and found Old Rinkrank inside it with all his gold and silver.

Then the King had Old Rinkrank put to death, and took all his gold and silver.

The princess married her betrothed, and lived right happily in great magnificence and joy.